By Nicholas You, Executive Director of the Guangzhou Institute for Urban Innovation

This article was delivered as a mini-masterclass during the Learning Forum at the UCLG Congress in Daejeon, South Korea on October 11th, 2022.

The power of storytelling: key ingredients to inspire your peers

“Persuasion is the centrepiece of business activity. Customers must be convinced to buy your company’s products or services, employees and colleagues to go along with a new strategic plan or reorganization …., and partners to sign the next deal. But despite the critical importance of persuasion, most executives struggle to communicate, let alone inspire. Too often, they get lost in the accoutrements of company speak: PowerPoint slides, dry memos, and hyperbolic missives from the corporate communications department. Even the most carefully researched and considered efforts are routinely greeted with cynicism, lassitude, or outright dismissal.” Storytelling That Moves People by Bronwyn Fryer

Telling a story is much more than it appears. Telling a story can make a big difference – it can inspire people, change people’s perceptions, and make people behave or act differently. Stories, throughout history, have been one of the principal ways to educate children and adults alike, to remind people of their past and therefore think about their present, and to construct the foundations for a better future.

Telling a story is much more than it appears. Telling a story can make a big difference – it can inspire people, change people’s perceptions, and make people behave or act differently. Stories, throughout history, have been one of the principal ways to educate children and adults alike, to remind people of their past and therefore think about their present, and to construct the foundations for a better future.

Browyn’s take on communications, whilst focusing on industry, is very pertinent to local governments and public affairs. Local governments – cities and regions – are different from companies in one aspect. Whilst they compete with one another just like companies, they are more than willing to exchange their trade secrets – namely their best practices and success stories. This represents a unique opportunity for peer exchanges– under the condition that the success stories are presented in such a way to foster learning.

The challenge lies with how leaders of cities and regions tell their stories. Local government leaders, just like CEOs of companies, tend to focus on “what they did or are doing”. Just like company reports, the focus is on metrics, namely number of houses built, kilometers of roads improved, quantity of waste removed, etc. The “story” sounds very similar to a company’s quarterly report. Instead of houses we have sales, instead of roads we have facilities, and instead of waste removed we have staff cuts (every pun intended!).

In summary, the way local government leaders tell their stories is not that different from how CEOs report on company performance. Both are presenting the rationale of what was successful. The problem with telling a rational story about what you have achieved is that your peers are arguing in their heads with all the reasons why local conditions would not allow them to do the same.

There are two key ingredients to storytelling that can help overcome this barrier.

- The first one is to unite an idea with an emotion. The best way to do that is by telling a compelling story. As Bronwyn states: “In a story, you not only weave a lot of information into the telling but you also arouse your listener’s emotions and energy. Persuading with a story is hard. Any intelligent person can sit down and make lists. It takes rationality but little creativity to design an argument using conventional rhetoric. But it demands vivid insight and storytelling skill to present an idea that packs enough emotional power to be memorable.”

- More importantly, if people can remember your story, they can remember what inspired them, what caused them to think differently about their own problems and challenges, and, ultimately, to seek a new path towards solving a problem. In short, to make a story memorable, invest yourself in the story. Tell your audience what made you “tick”, what made you dream or have nightmares. What and who compelled you to act! In other words – make it very personal. You are a leader and leaders, by definition, should inspire other leaders.

Local government leaders should, therefore, tell their stories differently. Instead of focusing on “what was done”, local government leaders should focus on “how it was done”. The key questions that will inspire others to learn from a good or best local government practice lies in a few simple principles.

Some key questions that will inspire learning from good practices:

How was the problem or challenge identified and by whom?

Presenters too often presume that a problem statement is enough. A good story traces the origin of the problem or the challenge. For example: Was there a crisis? If so, what was the nature of the crisis? Or was the problem a long-standing one and, if so, why was it not addressed before? Were there previous attempts that failed? What changed in people’s perceptions to want to solve the problem now?

What were the obstacles/difficulties encountered and how were they overcome?

People rarely learn from solutions. Solutions are like recipes without the cooking method. People learn from the process that led to the finding of the solution. It is the processes that are transferable, not the solution.

What worked well and what worked less well, how and why?

This is the core of the story. “Trial and error” is, by definition, learning. Painting everything as a brilliant success is boring and numbs the mind.

What has changed, who made the changes possible and how?

Change is the essence of problem-solving. In many ways change is the outcome, be it change in how an issue is perceived or in policy. What made the change possible is therefore a key takeaway of the story.

How were partners/stakeholders engaged?

Participation, be in the form of town hall meetings, hearings or planning exercises are a step in the right direction. But true co-creation and co-ownership depends on engagement. How were the partners and stakeholders mobilised? What stake were they given in the outcome? What resistance or reluctance was encountered and how was it overcome?

What would you do differently if you could start again?

This last question proves that the lessons have not only been learned but also internalized and can be used to go to scale or replicate the processes of change to other policies, programmes or projects.

Last but not least, make the story short

Six to 10 minutes are more than enough to tell a story leaving enough time for serious Q&A and discussion. It is the latter two that are the ultimate indicator that your story has piqued the interest of your peers and motivated them to learn more. In the case of a written story, 1 page to one-and-a-half pages should be enough (please see example below). The same story was presented orally in 5 minutes and used one visual slide (see below).

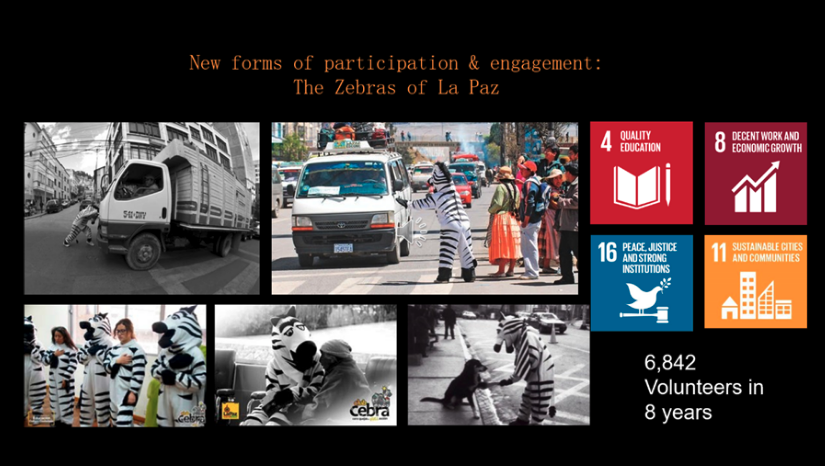

The “Zebras of La Paz”

Traffic in La Paz was a nightmare for any political leader: chaos, congestion and one of the highest levels of road accidents causing material and bodily damage in the region. For over a decade, various attempts at traffic control and policing failed to make a difference. Until, in 2001, the then city leader decided to use a completely different and innovative approach. The “Zebras of La Paz” is an initiative to raise public awareness on road safety. It is a very successful undertaking on two fronts: it actively involves highly vulnerable youth in a citizen (adult) education program. Some 300 youth at risk, between the ages of 12 and 20, are trained every year by clowns to become very unique “civic educators”. They are paid a minimum wage and are disguised as zebras, in reference to zebra crossings, and are present at all major crossroads during heavy traffic hours.

The aim is to change both driver and pedestrian behavior and to encourage both groups to obey traffic signs and rules. The outcome is less traffic congestion and accidents and, equally important, provides youth at risk with a unique opportunity to become active and responsible citizens.

A social worker I interviewed recounted: “the principal reason why young people drop out of school is because they fall behind in their schooling and nobody takes the time to help them catch up. They lose self-esteem, something gangs are very good at providing. The Zebras of La Paz have been put in a unique position of confidence and soft power – they make fun of adults in a comic way and they are considered heroes as they help the elderly and disabled to cross the streets!

The impact of this initiative, for a number of years, remained local but is now spreading to other cities across Bolivia as well as to other countries in Latin America. It is also going to scale as a new undertaking of the “Zebras” is to help raise awareness of and prevent bullying in schools.

The transformational nature of this initiative lies in its friendly and comic dimension and the innovative manner of engaging and integrating youth at risk. Youth are given a meaningful role in society, one which both empowers them and provides them with respect and dignity.

As a result, many of the 7,000 girls and boys who have participated in this initiative have continued their education and found decent jobs; a few have pursued higher education. This initiative won the Guangzhou Award for Urban Innovation in 2016 due to its simplicity, transferability and social impact. When asked what he would do differently, the mayor responded: “We should have started this initiative earlier”.

Nicholas You is a veteran urban specialist. He served as the senior policy and planning advisor to UN-Habitat and as the manager of the Habitat II Conference held in Istanbul in 1996. He is the founder and honorary chairman of the UN-Habitat World Urban Campaign Steering Committee, former think tank and thought leader for among others, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, Siemens, ENGIE and the Global Cities Business Alliance. He served for several years as an adjunct to the Center for Livable Cities, Singapore. He is currently the Executive Director of the Guangzhou Institute for Urban Innovation and co-Chair of the Open Green City Lab in Shenzhen. He regularly advises central and local governments, technology companies and civil society organisations on urban sustainability, urban governance and urban innovation and has written and co-authored key policy papers for the U20.

See also:

- Lifelong Learning and the Local Public Officer: Some Critical Reflections by Prof. Dae Joong, President of the National Institute for Lifelong Learning, South Korea

- The value of tracking the impact of peer learning by Catherine Anderson, Governance for Development Team Lead, The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

- The power of gamification: Designing and using learning games for local and regional governments by Gaya Blom, Program Manager at The Hague Academy